Federalism is not a sexy concept. I think that is unfortunate.

I can’t help but notice that with the rapid onslaught of authoritarian and totalitarian developments in Western Democracies over the past eight or so years, the United States has fared a little better than others. To limit ourselves to the Anglosphere, if England went crazy, Canada, Australia, and even darling little New Zealand went bat-shit crazy. Not that we in the States have come through unscathed, but we have come through inconsistently crazy (not that there aren’t those attempting to drag us all over the line).

Our Constitution, which the English, with their superior unwritten Constitution, liked looking down their noses at as rather unrefined and colonial, actually proved to have some hutzpah left in it. It allowed the courts to block some of the Executive’s malevolent maneuvers. The federalist structure of our government, which had been on a solid century-long slide into senescence and centralization of national power, actually showed some life under the attempt to fully impose a COVID regime. We actually got 50 different responses, from the full lockdown sort to the ‘we ain’t doin’ none of that crap’ variety, as the system was actually designed to give us. Since then, many states have been flexing their muscle to resist encroachments by the national government or to take action where that government has been willfully negligent in its duties. It’s enough to make you stop and (re)think.

Further, even when the issues are not presented in this way, many conflicts of interest in contemporary American politics are actually about federalism. When governors take actions contrary to national direction, or refuse to implement national policies, those are actually issues about federalism and where sovereignty (the ultimate right to make political decisions) actually resides. By the same token, when some champion of the extension of national power and authority, or attempt to remove the states from national politics, such as with proposals to abolish the electoral college, those are also issues of federalism. The same is true in Europe when it comes to the relationships of individual nation-states to the European Union or, at least sometimes, the degree of autonomy a community will enjoy in relation to the nation-state such as with Scotland or the Basque region.

American federalism

The American system of federalism is rather unique in that it represents an innovation over previous conceptions. Ultimately, we will wish to push back to the founding of those earlier conceptions. The US Constitution (1787) outlines the relationship between the national government it was creating and the state governments which were entering into agreement with one another to create that government. The third entity recognized is ‘the people.’

This provides the familiar structure of American politics revolving around the national government and then state and local governments. Federalism is normally associated with an attempt to safeguard liberty. The American example shares this concern, but really is meant to balance that considerably by establishing a strong central authority. The Articles of Confederation (1781) established a federal structure with a very weak central authority and had proven too weak, so it seemed, to deal effectively with foreign affairs and internal disruptions.

The revised federal structure both granted more powers to the central government and, more importantly, introduced an innovation. Traditionally, a federal structure would hold that the people create their local governments and then those governments come together to establish a federation between themselves. This federal authority, in turn, regulates the conduct of member entities but not the people directly. The US model weakens the intermediary entities (the states) by asserting that it is ‘We the people’ who are establishing the national government and grants that government in turn the power to directly subject individuals (not just the states) to national laws. Hence, the national government has the ability to impact individuals directly. This removes the functional aspect of the intermediary associations, weakening them.

Nevertheless, for at least the first hundred years of our history the national government was in fact relatively weak (compared to European states) and a lot of individual and local liberties were maintained. Writing in Democracy in America in 1835, Alexis De Tocqueville understood that the task Americans had grappled with was how to preserve the liberty associated with a republican form of government with the extensive size of the nation. Traditionally, political theorists such as Rousseau and Montesquieu had held that the preservation of republics entailed their being of limited size. Once extended too much, the individual desire for power and fame would override republican virtue. Despotic policies implemented by a faraway government would take too long to be felt by the populace and once felt would be too remote to effectively be challenged. In a small republic, the despotic action would be felt immediately and the people were close enough to authority to take effective action.

According to De Tocqueville, America had pulled off the trick. Americans had maintained the “habits of republican government” by centering most political decisions at the local (township) level and even the states were relatively small entities. The national government was yet strictly limited in its powers. He observed: “The Union is a great republic in extent, but the paucity of objects for which its Government provides assimilates it to a small state. Its acts are important but they are rare.”i

Anarchist federalism

Outside of the specifically American context, it is probably the anarchist tradition that has paid the most attention to notions of federalism. In The Principle of Federation (1863), Pierre-Joseph Proudhon outlined the perennial issue of politics as: “Political order rests fundamentally on two contrary principles; authority and liberty.”ii Unlike some later anarchists, he held that both principles were firmly rooted in nature and neither could be done away with. The issue was only how to reconcile them.

Proudhon understood federation as the voluntary and bottom-up coming together of a set of families, groups, or towns. As such, he saw it as the key to politics and could assert “the federal system is the contrary of hierarchy or administrative and governmental centralization which characterizes, to an equal extent, democratic empires, constitutional monarchies, and unitary republics.” Further:

Its basic and essential law is this: in a federation, the powers of central authority are specialized and limited and diminish in number, in directness, and in what I may call intensity as the confederation grows by the adhesion of new states.iii

In the early 20th century, the German mystical anarchist Gustav Landauer could sing the praises of a federative structure as pulling off this same sort of alchemy:

Society is a society of societies of societies; a league of leagues of leagues; a commonwealth of commonwealths of commonwealths; a republic of republics of republics. Only there is freedom and order, only there is spirit, a spirit which is self-sufficiency and community, unity and independence.iv

The basic vision seems to be an organic and voluntary association of various groups, which were voluntarily formed in the first place, to address issues of mutual interest and concern. Families joining together, unions joining together, other groups joining together, municipalities joining together, and eventually nations joining together to ensure peace. At least, that has often been the ideal and it seems like a fine ideal.

Finally, some form of federalism was also characteristic of many theories of anarcho-syndicalism. For instance, Rudolf Rocker can claim:

The organization of Anarcho-Syndicalism is based on the principles of Federalism, on free combination from below upward, putting the right of self-determination of every member above everything else and recognizing only the organic agreement of all on the basis of like interests and common convictions.”v

I believe it can be said that federalism, generally speaking, is the primary means of conceptualizing how a society would develop in a well-articulated way into a complex form of organization in a bottom-up fashion. As such, it promises to emphasize liberty over domination, decentralization over centralization, and localism over globalism or cosmopolitanism.

The birth of modern federalist theory

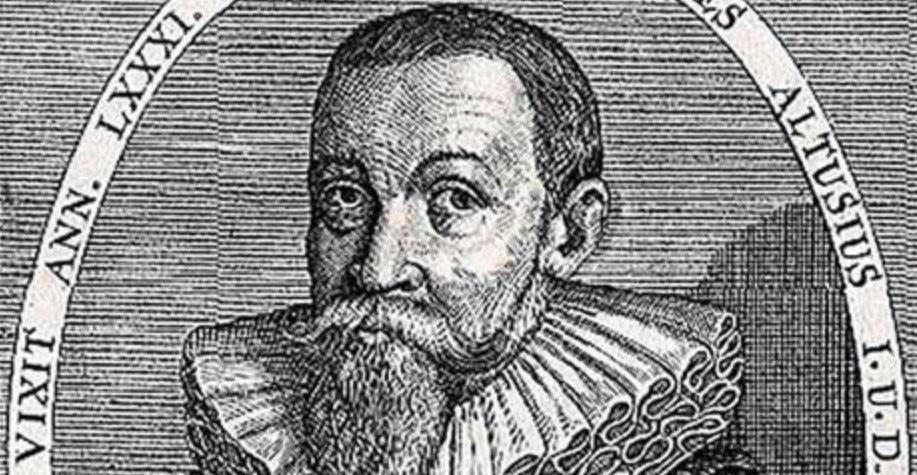

In the Holler, we tend to like to push back to the beginning of things. When we look to the beginnings of modern federalist theory in the writing of Johannes Althusius we get quite an interesting picture. Althusius was mostly unknown to the likes of the American architects of polity or the founders of anarchism like Proudhon and William Godwin. While his Politics Methodically Set Forth and Illustrated with Sacred and Profane Examples (1603) was at the center of debates around the nature of the state when it was first published, it fell from view until being rediscovered in the 1870s by German theorists thinking about the unification of Germany and then again fell into relative obscurity, receiving little attention as of late.

As modern nations began to emerge, theories about the nature of the state and of sovereignty took center stage. The jurist Jean Bodin established the first systematic theory. In The Six Books of the Republic (1576), he introduced the word ‘state’ in its modern meaning and provided a justification for absolute, centralized political authority, preferably in the hands of a monarch accountable “only to God.” Bodin was writing in the wake of the Bartholomew’s Day Massacre and of prolonged sectarian strife in France between Protestant Huguenots and Roman Catholics. His overriding concern was to formulate a theory of ‘undivided’ sovereignty so as to preclude the formation of factions which can engender civil strife. He explicitly sought to overcome the ideas of the Protestant ‘resistance to tyrants’ tradition, itself rooted in earlier Catholic natural law theory, which would have provided the justification for opposing a tyrannical government. Thomas Hobbes would take up much the same project writing in the aftermath of the English Civil War.

Althusius was likewise a jurist. He was born in an independent county of Germany and lived and studied in various places in Germany and Switzerland, himself being a Calvinist. He was the first to offer a systematic critique of the absolutist position. Though almost unknown today, he could rightfully be seen as the first modern anti-authoritarian.

He argued that sovereignty resides in the people and can never be fully alienated. Even more interesting from an egalitarian anti-modernist perspective, Althusius’ argument is thoroughly Aristotelian and Christian. That is, though he is living in the modern era and responding to modernizing developments in political philosophy and jurisprudence, he sees no need to jettison pre-modern ways of thinking and of conceiving the world. He provided a path for maintaining our cultural connection to pre-modern wisdom traditions; a path that was not in fact followed and which later thinkers would have to labor to attempt to rediscover.

Further, I think Althusius can be seen as providing a development of the Aristotelian line of thinking we looked at in my “Revolutionary Aristotelianism” essays that allows for an authentically naturalistic and organic way to think of complex societies in ways compatible with Aristotle’s emphasis on organic development, culture, virtue, and the common good. You may remember that there I had argued that the modern state fails to meet Aristotle’s criteria for a natural association and we had reviewed Alasdair MacIntyre’s critique of the modern state and of the capitalist market as incompatible with an Aristotelian ethics and with robust notions of human flourishing. However, neither Aristotle nor MacIntyre had provided a path to theorizing a complex natural society. I believe that Althusius can help us formulate a more satisfactory vision of an Aristotelian society in our contemporary context than any of the other attempts which accept the modern state as fitting within his theory.

What I will hope to show is that Althusius represented a different way of thinking about the development of larger and more complex societies in the modern era that was self-consciously critical of the theorization of the modern state and proposed an alternative model instead. This model emphasized organic development, decentralization, and strict accountability on the exercise of authority. Additionally, he can be very helpful in supplying a more satisfactory metaphysical grounding for federalism that can prove helpful in correcting or developing later federalist thinkers such as those noted above.

In the essays that follow, we will look carefully at the basic structure of Althusius’ theory. This should be useful in helping us think in naturalistic and organic ways about larger, more complex societies than either Aristotle himself or his medieval interpreters did. It will also shed light on how we might strengthen the liberty-preserving and humanity-nourishing aspects of existing federal structures such as those in the United States, Canada, Europe and elsewhere, and in understanding relationships with indigenous communities in various parts of the world.

i Alexis De Tocqueville, Democracy in American, in Theories of Federalism: A Reader, edited by Dimitrios Karmis and Wayne Norman, Palgrave, 2005, p. 152.

ii Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, The Principle of Federation, also in Theories of Federalism, p. 173.

iii Ibid., p. 178.

iv Gustav Landauer, For Socialism, translated by David J. Parent, Telos Press, 1978, pp. 125-126.

v Rudolf Rocker, Anarcho-Syndicalism: Theory and Practice, independently published edition, 2024, p. 65.

This essay was first published on Winter Oak.

Also see a companion piece by Peter D'Errico.

Well written! I always like to add that we didn't just have political federalism, part and parcel with that we had federalism in the economic and scientific/engineering spheres as well. And the results were powerfully positive.

Its a shame the world's only contemporary example of an advanced place that has a lot of federalism, China, may be leaping towards centralization (they've already gone a good amount of the way there over the past five years). Between roughly the early 1980s up until recent years, with its politically and economically decentralized system and democratic governance structures built around its broadly representative local parties who wielded control of local governments that had *real* power, China, despite not having the vote and some other key things, in some of the most key ways darkly ironically resembled the USA's Old Republic more than contemporary America does. However Xi and the special interest groups around him at the national center are trying to hyper centralize and dedemocratize, the recent 3rd Plenum declares the intent to eliminate any policy variabilities that have the effect of generating partial local trade protectionism and partial local capital inhibitors. But that variability and the democracy it enables has been the great enabler of China's success! I hope they fail.

Excellent. Thanks for digging into this in such detail. Definitely worth the long read. Waiting to learn more and get your synthesis (if you call it that) of the variables of federalism….

One note:

"The Articles of Confederation (1781) established a federal structure with a very weak central authority and had proven too weak, so it seemed, to deal effectively with foreign affairs and internal disruptions.”

I see ‘foreign affairs’ here primarily referring to relations / wars with Native peoples… and ‘internal disruptions’ similarly referring to the continuing resistance of Native peoples after their forcible ‘inclusion’….