Year of nineteen hundred and twelve

April the fourteenth day

Great Titanic struck an iceberg

People had to run and pray

– Blind Willie Johnson, God Moves on the Water

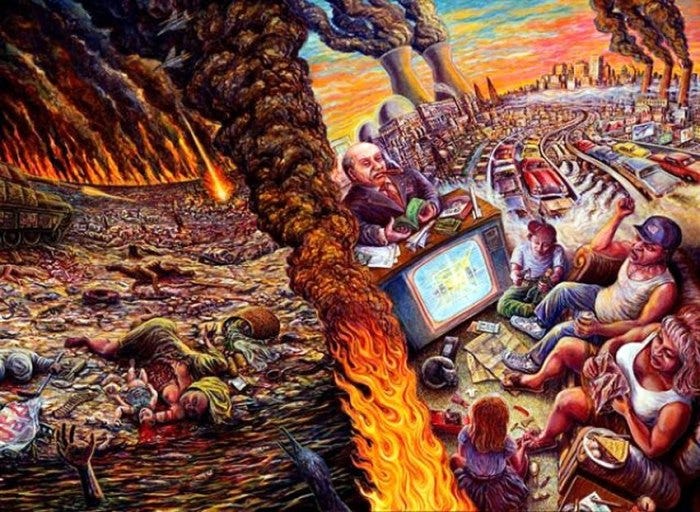

How do we get to the genuinely other side of modernity, and hopefully to some good version of that? Thus far we have looked at what we might term ‘constructive’ approaches. A radical critique of modernity coupled with a vision of a better alternative to work toward. Blind Willie Johnson’s song points to another possible path. To many at the time, the sinking of the Titanic was a warning against the human hubris embodied in the industrial age. She was to be one of the greatest accomplishments of that age, was named after Greek divinities, and was vaunted to be ‘unsinkable’. She was a symbol of humanity pushing too far. She was also an indication that, despite its great power and confidence, perhaps the modern world was more fragile than it looked. Perhaps modernity is strong enough to close off constructive efforts to transcend it, but perhaps not strong enough to preserve itself indefinitely. It is possessed of an incurable inner dynamic to transcend all limits and to always produce and consume more. Neither limited and fallible human beings nor a finite planet can sustain that forever (could not ‘transhumanism’ be seen as the attempt to transcend the limits of the human in fulfillment of the modern idol?). There is the sense that it must collapse under its own weight.

That may be the other way we end up getting to the other side. We could call this the ‘catastrophic’ approach. Modernity, industrialism, capitalism, globalism, the whole shebang collapses before it can be constructively transformed. That would not be a fun time. It could be a time of opportunities for humanity though. We might be like addicts who can’t quit their habit till they have some sort of breakdown. Though that is hard, and might kill them, they then get a chance to build a better life on the other side (assuming they survive the catastrophe).

“The Long Emergency”

One author I would place in the egalitarian anti-modernist camp who takes an approach something like this is James Howard Kunstler. I first came across his ideas back in the 1990’s via his critique of American urban planning, Home From Nowhere: Remaking Our Everyday World in the Twenty-First Century (1998). He critiqued the development of the American ‘suburb’ and the urban sprawl it creates. He is a ‘new urbanist’ and would much prefer livable urban neighborhoods, or small towns, to that which is not neighborhood, not town, and nothing, really.

More to the current point would be his 2005 book The Long Emergency: Surviving the Converging Catastrophes of the Twenty-First Century. It looks like there are plans to turn this into an updated feature-length documentary film as well. His basic thesis is that the modern world cannot sustain itself. He takes seriously the threat of climate catastrophe manifesting itself first in crises of food production and distribution (though in later works he sees food crises more likely to arise from other causes). There are also various societal dynamics that threaten, from global financial Ponzi schemes to cultural exhaustion. Probably most famously is his idea of ‘peak oil’. The idea here is that given that oil (and other fossil fuels) are finite and that the more of them you consume, the costlier it becomes to access the remaining reserves, there will be a tipping point where there is not sufficient cheap energy to keep our world running as it currently does. Further, cheap energy is the foundation on which the modern world is built and it was a bad wager from the beginning given that it becomes ever more reliant on a finite resource.

Kunstler recognizes that modernity is creative in many ways, hence, the long aspect of our current and ongoing emergency. But the catastrophic scenarios mount and the modern world can’t get itself out of the issues it creates without ceasing to be modern. Kunstler assumes that somewhere in the convergence of these scenarios, the ship will go down.

“World Made By Hand”

To supplement the more analytic approach he takes in The Long Emergency, Kunstler provides a dramatic portrayal of what a post-catastrophe world might look like in the form of a four novel series. Both the first novel and the series as a whole are called World Made By Hand (the first novel appeared in 2008 and the fourth came out in 2016).

The novels are set, mostly, in and around the town of Union Grove, Washington County, in New York’s Hudson valley. The time is “sometime in the not-distant future…”.i However, between now and then, much has transpired. There has been a prolonged war in “The Holy Land,” possibly over diminishing oil reserves, but that is not explicitly stated. The war had taken a huge toll in lives amongst the contending powers and had nearly exhausted their industrial capacities. Then terrorists ignited ‘dirty’ nuclear bombs in L.A. and Washington, D.C. This precipitates the rapid collapse of American society with a military coup headed by a rogue general who is then overthrown by “more constitutionally minded” generals, but all that is anticlimactic as society ceases to function along modern lines. In the wake of all of that, the “Mexican Flu” and other maladies drastically diminish the population (by about 75%).

We hear rumors about how other parts of the planet are faring. In later novels we learn that there is an attempt to reconstitute something of a national government in the Great Lakes region and that the American South has been ravaged by racial conflict. A fascist regime headed by a female ex-television evangelist is centered in Tennessee and an African-American republic centered in the deep south, led by Milton Steptoe, who had run a check-cashing empire, is proving more than a match for them. We’ll focus our attention on the central happenings around Union Grove, which serves as a sort of lab for social experimentation in the new world.

On the first page, Kunstler signals that there is a natural basis for human society, which is reemerging in the post-apocalyptic setting when he has a character observe: “Now and then, the fireflies pulsed in unison, mysteriously, as if they all agreed on something we humans didn’t know about.”ii A general characteristic of the new world is the reappearance of much that is mysterious, along with a bounce back by nature (the streams are clean again and fish populations are rising; trees and other growth are reclaiming the vast pads of concrete). We are eventually introduced to a (good) witch who seems to practice effective earth and sexual magic. We have a mysterious cult leader with supernatural powers. Kunstler often uses female characters to illustrate this reemergence. The above mentioned fascist tele-evangelist may represent the dark aspect of this.

In my reading, the story centers around a handful of micro-societies, each attended by their key and representative characters, which spring up in the wake of the collapse.

Civic Community

This is represented by the town proper of Union Grove. The main characters here are Robert Earle, a carpenter and eventual mayor of the town, Loren Holder, the First Congregationalist Pastor (who is eventually ‘healed’ by the above-mentioned witch), and Ben Deaver, a relatively wealthy farmer on the outskirts of town who utilizes hired labor to work his farm.

Characteristics of life in the civic community include doing things through discussion and mutual consent. Also, civic community is ‘impersonal’ enough to allow people who might be outsiders in other forms of society to find their niche, represented by a homosexual librarian and portrait painter and a store clerk who has Down’s Syndrome. The civic community lacks decisive leadership (something all the other models possess), but seems best at reaching overall decisions.

Feudal Community

This possibility is represented by Stephen Bullock, formerly a Duke educated attorney “with the look of Roman authority.”iii Bullock is an authoritarian (somewhat harsh, but ultimately benevolent) leader of something like a feudal fiefdom. He already possessed a large estate when the world went wrong, and in the lead up was wise enough to acquire the sorts of items that would be essential in the new world. His estate still has limited electricity, which has all but disappeared from the rest of the world.

His “servants” are there voluntarily. His version of society provides the most material goods and greatest security, though the least freedom. Like a feudal Lord, Bullock provides safety and succor, demanding obedience and service in return. It is definitely one-man rule. As the novels progress, we get the sense that this form of society is relatively stable, as long as its charismatic leader remains, but suffers certain inherent limitations that mean it will not work as a generalizable model.

Religious Community

This possibility is represented by Brother Jobe who is presented as something of a red-neck huckster, but who is eventually revealed to have also been a Duke educated attorney and is a genuine spiritual leader. However, the real leader of the “Church of the New Faith” community is, arguably, a shadowy female character who can see the future and somehow seems to birth new “New Faithers” in litters, an essential function given that the males are largely sterile due to having been located near Washington, D.C. when that nuclear bomb went off.

Life in this community is centered on unity and intensity of faith, along with charismatic leadership. Though there is conformity in faith, Kunstler presents this community as one that is creative (though the New Faith brethren and sisters have sexual relations, they are sterile; Kunstler may be playing off traditional monasticism with its combination of sexual chastity and outward creativity). Brother Jobe is overseeing the breeding of various useful animals, especially Mules. The “New Faithers” form a symbiotic relationship with Union Grove and often possess the skills the town needs and, with the establishment of a bar, sparks a renewal of the town.

Marginal Community

This group is represented by Wayne Karp and his “general supply”. Karp’s followers are former “motorheads;” even in the “old-timey, old times,” as Brother Jobe calls them, they were people on the margins of society. In the new world they run a semi-criminal, though ultimately needed, operation of scavenging the rest of the world for needed items that can no longer be manufactured.

Life in this group is volatile and often violent. Yet, it ‘fits’ for many who do not find they can accept any of the other models on offer. ‘The general supply’ is outside the ‘law’ of the other communities. It is organized more on the lines of a gang.

Social ecology

Kunstler centers the civic option, both in terms of focusing the story on it and in the sense that he seems to think that it is the option that most ‘has a future.’ However, all the options are presented as having strengths and weaknesses. All represent modes of sociality that have proven durable at various points in history (more durable than our own highly industrialized society) and Kunstler presents them all as possible options in a no longer modern world. Further, they are all shown to be able to cooperate productively with one another. There is a diverse social ecology operating here. That is probably a healthy vision to have of a non-modern world; no ‘one size fits all’ solutions.

A character observes “everything is local now.”iv It could also be said that everything is human scaled. The potential big problems lurking are associated more with the attempts to recreate larger societies like the fascists in Tennessee. Kunstler likes to imagine a variety of genuinely human options for his world and all might feel more authentic than our current situation. The characters have to come to grips with continuing to live in a world that is diminished in many ways from their previous experience. They seem to have a consensus though that the new times are actually better times in many ways. The basis for this is summed up in a conversation between Robert Earle and his girlfriend (both of whom have been widowed by the harsh new realities):

(Robert) There’s goodness here too.

(Britney) Where is it?

(Robert) In all the abiding virtues. Love, bravery, patience, honesty, justice, generosity, kindness. Beauty too. Mostly love.v

Perhaps that is the power that manifests itself in human relationships that is akin to whatever it is that empowers the fireflies to operate in harmony. To the extent that Kunstler might seem to long for a post-catastrophic world, it is probably because so much that is not real and enduring gets stripped away so that the light shines more clearly on what is of genuine value.

Catastrophe and the imagination

Kunstler’s World Made By Hand quartet would fit in the ‘post-apocalyptic’ genre. As that appellation suggests, there is a reflection here of the apocalyptic literature of many ancient religious traditions that assumes that that which had a beginning will have an end. However, the idea of humanity continuing to live in a time after the catastrophe seems to be roughly coterminous with modernity itself, with the first examples of this genre appearing in the 1810s and 1820s. Byron and Mary Shelley both wrote works that could fit in this genre.

Certainly, the pace of the production of post-apocalyptic fiction (in literature and film) has picked up in recent decades. The 1970s had all those natural disaster movies (and they haven’t stopped coming). The 1980s had aliens and technological tyranny. From the 2000s forward it seems the genre focuses more on human caused catastrophes and human-against-human post-apocalypse scenarios. This is especially true in the world of ‘young adult fiction’: The Hunger Games series and The Purge series stick out. Of course, our whole fixation on zombies fits here as well. It is as if the culture was, mostly subconsciously, registering our predicament (and fate?).

What’s more, one can sense, at least in some cases, the ‘end’ is not looked toward with unmitigated dread, but with something of a longing. This, I think, is the case with Kunstler. In his occasional writing he constantly sees a new crisis looming which surely must bring consequences which we will not be able to ignore, but the ‘long emergency’ is awfully long.

However, as a literary genre, it is also one means by which we can project our vision of the good society. Kunstler also does this. It can provide a mental fresh-start situation within which to dream. As a possible reality, it is more sobering, but perhaps no less filled with hope.

i James Howard Kunstler, World Made By Hand, Atlantic Monthly Press, 2008, title page.

ii Ibid, p. 1.

iii Ibid, p. 77.

iv Ibid, p. 15.

v Ibid, p. 226

This essay was first published on Winter Oak

His books have been on my reading list for a while. Peak oil is so unfashionable now, I don't think many grasp that the end is written in stone. Jim likes to ask which if the straining structures will break first but they are all faces of the same thing; the economics depends on the physics and the violence (including the risk of nuclear conflagration) springs naturally from the strain produced there..

Paul wrote in a comment (on the last of his own articles) that he takes heart from the fact that the AI prison world cannot truly come into being as envisioned. There's so much of that ilk we can let go of. Technocracy is shit, no doubt, but it's also so dumb it's comical. This is what I meant when I suggested we focus on what is physically possible. A world made by hand is, while a world made by robots is not.

I find Jim somewhat limited by his political imagination but it's a consoling vision nonetheless (aside from the billions who have to die!)

you do a good job explicating these books and ideas... thanks