ROUSSEAU’S REVIVAL (EGALITARIAN ANTI-MODERNISM PART 4)

Outright opposition to modernity is often dismissed as backward-looking or “reactionary” and associated with a rigidly hierarchical or aristocratic outlook. But there is another tradition of resistance to the modern world that has very different ideals and can serve as the basis of an old-new radical philosophy of natural and cosmic belonging, inspiring humanity to step away from the nightmare tranhumanist slave-world into which we are today being herded. In this important series of ten essays, our contributor W.D. James, who teaches philosophy in Kentucky, USA, explores the roots and thinking of what he terms “egalitarian anti-modernism”. (Paul Cudenec’s preface to the series on Winter Oak).

Ya’ll got to have religion, yeah, I tell ya that’s all

Now he can go to college

Go to the schools

Haven’t got religion he is an educated fool.

– Sister Rosetta Tharpe, That’s All

How does religion fit into egalitarian anti-modernism? Really, there is great diversity here. Some, like GK Chesterton, will want to bring forward pre-modern religious traditions. Others will reject institutional religion in total, but seek spiritual values elsewhere. For instance, William Morris is enamored of the Middle Ages, but not so much with its Roman Catholicism. He sees value in the craft guilds, gothic architecture with its forms taken from the natural world, and the examples of plebeian resistance to oppression manifest in peasant rebellions. None accept the thinned down, mercantilist, and basely materialist worldview of modernity though. Rousseau represents an option somewhere between these poles.

By traditional standards, Rousseau is a religious radical. By Enlightenment radical standards, he might be a bit conservative. Jean-Jacques’ religion (or the religion he advocates) is along the lines of Enlightenment Deism. However, one senses he means it a bit more. He was born and raised in the Calvinist atmosphere of Geneva, but converted to Roman Catholicism when, as an adolescent, he moved to France and came under the influence of Madame de Warens, who served as his lover, while also fulfilling many of the functions of a mother. C’est la vie.

He outlines a basic philosophy of religion, consistent with reason, but drawing more on emotion and intuition than typical of the philosophes. Though he was persecuted as an innovator in the religious sphere, in the intellectual context within which he is operating, I rather think of Rousseau as shoring up a basis for the continuing relevance of religion in the modern world. He is convinced that a simple, but substantive, religion is necessary for both social and individual order and flourishing. Not to mention, to liberty. He is far from being a fundamentalist, but he isn’t a secularist either.

Civil religion

In the last chapter, save the one paragraph “Conclusion,” of On the Social Contract (1762), Rousseau takes on the issue of civil religion. His thought here has been influential on the likes of Robert Bellah (Habits of the Heart) and other recent communitarian thinkers. Here he lays out a basic typology of the ways in which religion can be related to civic life. He goes to pains to discountenance Christianity as a viable civil religion based on both its exclusiveness and its ‘other worldliness’. However, he also is sure to distinguish what he takes the be the true religion of the Gospels from institutional, historical, Christianity (more on this later).

For Rousseau, the basic function of a civil religion is to “make him [the citizen] love his duty…”.i The requirements of civil religion, though, should not go beyond what is necessary to reaffirm humanity’s “sociability”. To this end, he outlines the basic “positive dogmas” of a good civil religion:

“The existence of a mighty, intelligent, and beneficent Deity who is prescient and providing, the existence of the life to come, the happiness of the just, the punishment of the wicked, and the sanctity of the social contract and the laws [representing the ‘General Will’ through radically democratic mechanisms].ii

The sole “negative dogma”, the only prohibition, is against “intolerance.”iii

The purpose of Rousseau’s civil religion is essentially to provide the metaphysical framework within which it makes sense to perform one’s social duties when temptations exist to do otherwise. He gets that the just do not always prosper here below and the oppressor is not always checked. He feels the need, for the workability of civil society, that citizens believe some fundamental truths of the moral life. Ultimately, justice pays. Ultimately, the evil do not prosper. Even modern societies need these ‘old fashioned’ notions to form a suprarational social glue. Reason alone is not a sufficient basis for sociability and just order. While Rousseau sees society arising out of a ‘social contract’, he sees that as not sufficient to maintain good social order and liberty. People need a vision of the goodness and coherence of existence itself to guide their social practice. Here Rousseau is clearly passing beyond the nominalist framework of his contemporaries.

Personal Faith

In that part of the Emile; or On Education (published in 1762 and publicly burned in Paris and Geneva that same year) known as ‘The Savoyard Vicar’s Profession of Faith’, Rousseau outlines what he claims is the statement of faith of a Roman Catholic priest whom he knew; possibly the priest that accepted him into the church. However, it is widely held to be Rousseau’s own statement of his personal faith.

He presents the priest as a person with “common sense and a profound love of truth.”iv He deduces just a small number of theological presuppositions. His method is pragmatic; what is helpful and not contrary to reason will be adopted. These dogmas are the immortality of the soul and the existence of a Supreme Being. The immortality of the soul ensures, as does his civil religion, the opportunity for the good to find consolation (at least in the eternal memory of having done well, whatever the temporal consequences) and the evil to regret their evil actions. Existence needs to make moral sense if we are going to live meaningful lives.

The Supreme Being undergirds a trust in the fundamental order of Nature and existence. Things make sense, morally and intellectually. Of primary importance for Rousseau is the reality of Conscience. We can assume God intended mankind to be free (since we experience free will and love liberty). Reason is not a sufficient guide to life; it “deceives us too often”.v “Conscience is the voice of the soul, passions are the voice of the body”.vi Thus Jean-Jacques, betrayer of his own progeny. Yet, we should note, Conscience, not Reason, plays the ultimate role of providing guidance in our moral lives. It is in following the dictates of Conscience, which includes that natural “Pity” Rousseau saw deeply imbedded in our nature, that our liberty and our sociality can be reconciled. Rousseau would have agreed with the sentiment of the American Blues icon quoted at the opening of this essay. Religion does not fit well with Enlightenment modernity, but it is far from clear that we can navigate satisfying and coherent lives or build cohesive and just societies without some sense of the ultimate to undergird our moral sentiments.

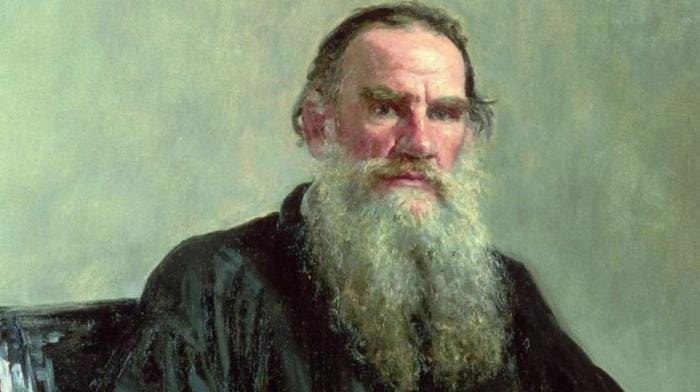

Rousseau’s Russian Disciple

Leo Tolstoy (1828-1910) recognized his debt to Jean-Jacques. I see in his account of his faith, a development along the same lines, though into deeper territory, of the path started by Rousseau. In his A Confession (1880), Tolstoy recounts the loss of his childhood faith. An aristocrat, he added fame and notoriety (with the likes of War and Peace and Anna Karenina to his credit) to noble birth and enjoyed all the sensuous pleasures of life. Yet, he felt life was nihilistic and was driven to the verge of suicide. He noticed that the poor simple peasants working his estate had no such malady, and though economically and materially challenged, possessed a strong conviction that life was good and lived lives of meaningful purpose.

This set Tolstoy to inquire into the faith of his serfs and to study the religious faiths of the world’s many civilizations. He comes to the conclusion that “rational knowledge” only undermines meaning. He identifies an “irrational knowledge,” that he terms “faith,” which can sustain his need for meaning.vii For Tolstoy, ‘faith’ is largely the ability to affirm ‘life’ despite reason’s condemnation: “where there is life there is faith.”viii Faith is the affirmation of life, which goes deeper than our discursive reason. A ‘Yes’ to existence from which we may then reason fruitfully, but a commitment that does not itself result from reasoning.

Tolstoy’s method was to look to the people he could not avoid seeing were ‘good’, then try to believe and live as they lived. He equally discerned goodness in the Russian peasantry and in the great religious teachers like the Buddha, Confucius, Jesus, and Mohamed. He eventually came to outline a universal faith he felt was characteristic of all good people. In “What is Religion” he recounts how, under the light of eternity and infinity, he came to understand the brotherhood of all people and, hence, the supreme value of love. This is the core of his Christian anarchism. He understands ‘religion’ as whatever binds a person to the infinite and eternal, and, hence, to the affirmation of life which is really an affirmation of existence. It is only in the light of this ultimate existence that fundamental human equality and value can come to the light (for the simple reason that by any finite standard of measure we are in fact not equal, not equivalent, but quite different).ix

Like Rousseau, he comes to believe that luxury can be enjoyed by some only at the expense of oppressing others. In works such as “Religion and Morality” and “The Law of Love and the Law of Violence,” he articulates how he sees ‘morality’ as the deduction of necessary consequences of behavior from the perspective of ‘religion’ (and religion, so understood, as the necessary basis of morality). We are related to ultimate existence (which is good). Acceptance of this affirmation is faith. The way of life that stems from that is morality. It is this basic religion which centers the ethic of love that both Tolstoy and Rousseau understood as the simple ‘Gospel’ faith, as distinct from institutional Christianity.

Rousseau and Egalitarian Anti-Modernism

According to Tracy B. Strong, in Jean-Jacques Rousseau: The Politics of the Ordinary (1994), the key to understanding Rousseau is to see he is attempting to rescue ‘ordinariness’. He is exploring the space between our isolated selves (Nature) and the transcendent. This is the space where we live out our lives with others and try to work out what it is to be human.

Rousseau thinks this can best be done by keeping in touch with what is common, in the double sense of shared and ordinary. It’s not in the fancy logic of the professional experts or the fancy theology of the theologians. It’s not in the ‘high culture’ of the educated. It’s in the simple longings of the heart and the innate goodness of ordinary people. This is how he set about to “defend the cause of humanity.” The fully human entails liberty, for ourselves and others. It entails achieving authenticity and overcoming hypocrisy and oppression. It entails recovering the simple virtue of ‘natural man’, ‘barbarians’, and ‘peasants.’

To do any of that will require a fundamental rejection of many of the sacred cows of modernity, and of all of its lies, and nothing short of a revolution. Rousseau has kickstarted a tradition of radical critique that still helps us see to the heart of modernity and see through its pretentions to glimpse a more wholistic alternative. In the essays which follow, we will now begin to look beyond Rousseau to later egalitarian anti-modernists.

i Jean-Jacques Rousseau, The Essential Writings of Rousseau, translated by Peter Constantine and edited by Leo Damrosch, The Modern Library, 2013, p. 226.

ii Ibid, p. 226.

iii Ibid, p. 226.

iv Ibid, p. 270.

v Ibid, p. 276.

vi Ibid, p. 276.

vii Leo Tolstoy, A Confession and Other Religious Writings, translated and edited by Jane Kentish, Penguin, 1987, p. 50.

viii Ibid, p. 53.

ix Ibid, p. 91.

This essay was originally published on Winter Oak