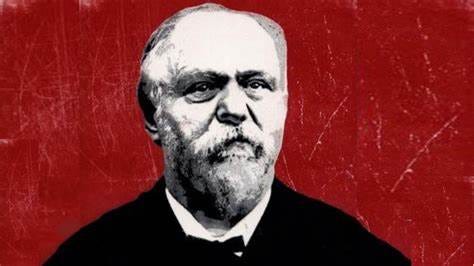

There are such things as dangerous ideas. Essentially, these are ideas that contain at least some truth and seek to operate, as Friedrich Nietzsche put it, ‘beyond good and evil.’ They are never quite licit. The conception of political ‘myth’ formulated by Georges Sorel (1847-1922) is one such idea.

Myths touch on deep aspects of our humanity. Karen Armstrong, in A Short History of Myth (2005), denotes at least five things a mythology will typically include:

The experience of death;

Association with rituals;

A confrontation with “extremity,” forcing us beyond our actual experience;

Guidance on how we should act;

A connection to “another plane” represented by “the perennial philosophy.”

It is through participation with the divine world via the myth that humans learn to fulfill their potential. What might be the political implications of myth? Sorel’s account will reflect this traditional world of myth, but will draw it down into the realm of power and politics and instrumentalize it.

Sorel seems to have largely slipped below our intellectual radar. I find only one recent English language video regarding him on YouTube. His appearances in academic journals are few and far between. Recent republications of his work available on a large online book retailer include two small presses: one socialist-anarchist the other hard-right reactionary.

Sorel kept evolving as a thinker. At different times, he was heavily influenced by the thought of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (this influence was enduring), Karl Marx, Benedetto Croce, Friedrich Nietzsche, Henri Bergson, and William James. He was in turns a never very orthodox Marxist, an anarcho-syndicalist, an integral nationalist, and a supporter of Lenin and the Bolshevik revolution. After his death, an Italian Fascist journal edited by Benito Mussolini (who had himself been a socialist and a syndicalist earlier in life) proclaimed fascism as the ultimate fulfillment of his ideas.

To make sure we don’t pigeonhole Sorel, it should also be noted that his thought was at the same moment being taken up and utilized by the Italian Communist Antonio Gramsci, who would later die in a Fascist prison.

A satisfactory explication of his ideas (which I don’t believe has been written yet), would take at least a volume. Here my aim is much more limited, recognizing there is much else to be considered and there is a lot that pretty much anyone could find problematic in his thought which I will mostly pass over.

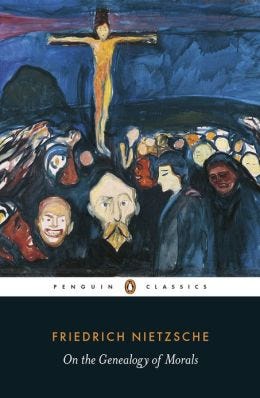

I will focus in on his conception of ‘myth’ and the role it plays in his theory of revolution. However, never one to be stingy, I will preface this with a look at another dangerous idea, that of Nietzsche’s ‘master morality’, and examine how the former both applies and transforms the latter, so as to provide some larger context for the Sorelian idea.

Moral Genealogy

In On the Genealogy of Morals (1887), Nietzsche seeks to give us an historical account of moral terms like ‘good’ and ‘evil’ without reference to any transcendent moral or metaphysical reality. On his view, historical moralities will be seen as expressions of will. Their impact, then, will be an expression of power: the ability to impact the values that will be accepted and become efficacious in the world.

In a sense, this completely undercuts any actual ethical content of morality. Or, it seems like it should. Nietzsche still holds to values which he clearly prefers and believes have some veracity. His new quasi-ethical principle will be ‘life’: moralities which are expressions of will which affirm ‘life’ will be seen as better, and more importantly, anti-decadent (so, the ultimate standard may be aesthetic). Moralities which are just as much expressions of will but which are anti-‘life’ will be exposed as hypocritical and decadent.

Nietzsche boasts:

“I am an opponent of our modern, effeminate ways, our ‘delicacy of feeling….’”

This strategy is reductive in that the ‘higher’ (morality) is explained in terms of the ‘lower’ (will and power), so this is a typically modern move. That this effectively represents a deconstruction of morality, and in exposing the operations of power relations as the ‘real story,’ it is also an expression of post-modernity; what has been termed a ‘hermeneutics of suspicion.’

On Nietzsche’s unpacking of things, the history of morality is one of degeneration. All civilizations are dominated by an elite: either a “knightly” aristocracy or a “priestly” aristocracy. The historical trend has been for knightly aristocracies, with their “master” morality, to be replaced by priestly aristocracies with their “slave” moralities. The society of barbaric Germans is his main model for a master morality, but the ethos of any warrior society should fit in as well. Amongst priestly aristocracies, he references the Brahmin caste in India, the Jews, and most specifically Christianity and the Church. The latter religion is his primary target as being most relevant to nineteenth-century bourgeois European society.

What characterizes master moralities is that their values express the ‘Yes’ to ‘life’ which informs the moral codes of warrior aristocracies. Their values are expressions of their robustness, strength, and will to dominate. A knightly aristocracy develops an ethos in which the following equivalences prevail: good=aristocratic=beautiful=happy=blessed by the gods.

For Nietzsche, this represents a free-spiritedness which is not afraid of willing and expressing itself. It is authentic.

Priestly aristocracies, on the other hand, wish to wield power but lack the overt force of the knightly aristocracy. Hence, they fight surreptitiously and in bad faith. Their motivation is that of resentment. Their method is to perform a “transvaluation of values” on the master morality of the warriors. The resulting slave morality turns all those values on their heads. Strong, powerful, violent, willful, glorious, etc… all come to be seen as evil, not good. One can think here of the Beatitudes extolled by Jesus in the New Testament: blessed are the poor in spirit, blessed are the persecuted, the meek shall inherit the earth. Those are not the values of a military aristocracy, but the opposite. On Nietzsche’s reading, this is no less an expression of will than was the counter ethos, but is an expression of the will of the weak but clever. It is a ‘No’ to life as joy in expression of its own power. As such, this morality will also be anti-life: an ethic of restraint, care, chastity, compassion…all very bad things for Nietzsche.

“The slave’s revolt in morality begins when resentment itself becomes creative and gives birth to values…”.

By exposing the underlying resentment behind the dominant slave morality, Nietzsche hopes to open up the possibilities of a new heroic ethos. This will not be of a warrior aristocracy in the old sense, but of a new spiritual aristocracy of those, like Nietzsche, eager to will new values.

Myth and Violence

Sorel largely accepted and built upon the Marxist analysis of history as the history of class struggle. However, he did not accept Marxism as an exact science. He did not think the future was determined. Socialism was not inevitable.

Further, he thought the motivation to revolutionary activity depended on ultimately non-rational factors.

As James Burnham explains:

“In contradistinction to the allegedly ‘scientific socialism’ of the official parties, to their elaborate programs of ‘immediate demands’ and desired reforms, to their lengthy treatises on how socialism will be brought about and what it will be like and how it will work, Sorel insists that the entire revolutionary program must be expressed integrally as a single catastrophic myth: the myth, he maintains, of the ‘general strike’.”

Sorel’s most prominent modern translator and interpreter, John L. Stanley, roots this vitalist element not only in the thought of Nietzsche but ultimately in that of one of the early fathers of modern anarchism, Proudhon.

He quotes Proudhon at length:

“Man first dreamed of glory and immortality as he stood over the body of an enemy he had slain. Our philanthropic souls are horrified by blood that is spilled so freely and by fratricidal carnage. I am afraid this squeamishness may indicate that our virtue is failing in strength. What is so terrible in supporting a great cause in heroic combat, at the risk of killing or being killed […]? Death is the crown of life. How could man […] have a more noble end?”

According to Stanley’s interpretation, Proudhon is saying that it is only through heroic action that a good and just society can be brought about.

It was in Reflections on Violence (1908) that Sorel developed his conception of myth.

There he writes:

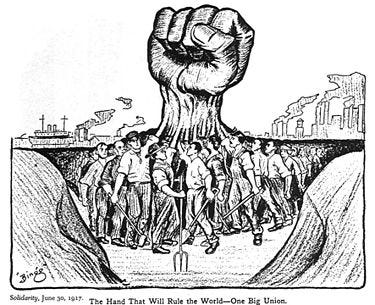

“[M]en who participate in great social movements represent their immediate action in the form of images of battles assuring the triumph of their cause. I proposed calling these constructions myths… the syndicalist general strike and Marx’s catastrophic revolution are myths.”

He is careful to distinguish a myth, in this sense, from either a theory or a utopia. Both of the latter are essentially intellectual matters of words. This alone is not sufficient to steel people for revolutionary conflict. Consequently, according to Sorel, those who are primarily motivated by these intellectual constructs will tend towards reform and compromise. These intellectual constructions are the province of political parties and professional politicians, neither of whom Sorel respected or thought capable of revolutionary action: they would tend to look at problems as calling for administrative and bureaucratic, ‘rational,’ solutions. Revolutions could only come from the masses.

Sorel observed that:

“Current revolutionary myths are almost pure; they permit the understanding of the activity, sentiments and ideas of popular masses who are preparing to enter into a decisive struggle; they are not descriptions of things but expressions of the will.”

A myth is more a matter of images than of language. Sorel argues that myths arise from instinctual sources in our individual and collective psyches. He is deeply skeptical that a science of socialism can tell us anything about the future of society: the future is not predictable. Hence, no scientific theory can guide the revolutionary masses. What is needed is a myth which both arises from their struggle with the foes they are confronted with and directs them to future oriented action. Myths embody “the mass of sentiments which correspond to the various manifestations of war entered into by socialism against modern society.”

So, it will not be Marxist dialectical materialism which throws the proletariat into violent struggle but the myth of a general strike which will concretely move them to militant action because it both expresses and stimulates the sum total of their sentiments and their will toward confrontation.

For Sorel, the instrumental function of myth is then to move the masses towards a violent confrontation with their society, its structures, and elites. However, violence has a very specific meaning for him. He contrasts it with ‘power’ where that term refers to the force used by dominant elites to exercise their will on the masses and ‘violence’ is the force exerted by the masses to contest and ultimately destroy the ‘power’ of the elites.

In this special sense, violence, or more specifically, the preparation for the exercise of violence in the hearts of the revolutionaries, is morally salvific. With Nietzsche in mind, he says that the proletariat cannot achieve revolution if it remains caught up in a “morality of the weak.” They must, collectively, adopt a morality of the strong.

“It is to violence that socialism owes the high moral values by which it brings salvation to the modern world.”

We can now see that Sorel has much the same project as Nietzsche. He wishes to morally revitalize the modern world through an act of will which constitutes new heroic values. However, he has changed the agent of this accomplishment. The revolutionary proletariat has been substituted for the spiritual aristocracy. The role of myth in this scheme is to provide the inspiring image of the violent encounter which will call the revolutionary to violence and sacrifice to boldly create a desirable future.

This analysis also helps to explain the religious, spiritual, and mythic dimensions that form around revolutionary movements. There really is a participation in the mythic going on. Revolutionary movements encounter death in the form of that movement’s martyrs and in the desire for violent confrontation with the established order. They develop their own rituals of activism. They move their participants beyond the realm of their current experience to the projected experience of the crucial confrontation and guide their action in that direction. Further, they take on cosmic significance: the final triumph of goodness and justice.

Moral Risk

If we believe there is something real and eternal to moral values, we cannot help but see this instrumentalization of morality, in its Nietzschean or Sorelian forms, as problematic. To a moral realist, someone who believes moral principles and values have objective existence, one places justice (or moral rightness) ahead of success. If one loses while maintaining their fidelity to these principles, at least it will have been a ‘noble cause’ one fought for. Better that than to sacrifice justice to gain an ignoble victory. The strict vitalist risks losing their bearings.

And yet. There is something to be said for victory. There is something true in these moral theories of Nietzsche and Sorel. Whether it is through the ‘will-to-power’ of the former or the ‘violence’ of the latter, existential conflict does produce and develop certain genuine virtues, like courage, the willingness to sacrifice oneself for a larger cause, in addition to others. Further, if one feels that all the moral energy has largely ebbed out of one’s society, the restoration of these virtues through conflict may well be morally and culturally salutary.

However, that cannot be the whole story, as both these thinkers more or less seem to think it is. Might actually does not make right. Or more specifically, even if the exercise of power and violence in a cause can elicit certain heroic virtues, that does not make the cause itself just or right. We can imagine people fighting for the most immoral cause in the world: they may well develop a form of courage and accept sacrifice. Those are still good things (though I think their goodness is seriously diminished by misemployment). Yet, no matter how great the virtues developed fighting for such a cause, it remains evil. Will, power, violence, heroism, etc… do not, in fact, create value.

So, here precisely is where the danger lies in these sorts of ideas. We may forget that people can act admirably on the behalf of bad causes. That is the negative side of the dilemma. If this were the whole story, we would do well to never venture forth on risky business.

The other side of the story is that a good cause which is never fought for is impotent. Winning is not bad. That would indeed be a very transvaluative idea to hold.

A further moral complication: even a good cause is never a perfect cause. They are all flawed. Further, even to the extent that a cause is good, if it requires the use of violence on a massive scale, the innocent will end up suffering as well.

In the complex world of our social relations to one another, I would suggest we neither need to assume the false notion that struggle itself makes the cause good, nor on the other hand should we spurn the notion that because the fight for the cause will be morally gray, we should abstain from the fight. That would be cowardice.

Tomorrow’s Myth

To the extent that Sorel’s conception of political myth is true, we would like to know what is the myth of the current struggle we are engaged in? Sorel is clear this is not something you get to just ‘make up.’ The myth emerges from the sentiments and aspirations of the revolutionary group. They have to authentically emerge from the genuine feelings and strivings of that group. Yet, they still have to be named, formed, and refined: he is less clear on how this does or should happen. Further, it identifies who their enemy is that is to be struck. Then, it must picture what would be the complete victory of the revolutionary group over their enemy. That, and not theories, according to Sorel, is what can move a group to revolutionary action.

If we look at the actual political terrain we inhabit, it seems the revolutionary group would include all ‘freedom-loving people.’ That is, so far, less defined than ‘the proletariat’ or ‘the nation’ were in earlier struggles. The sentiments and aspirations of this group would include, of course, freedom. I would suggest also implicit is a demand for dignity and fair treatment. There is also, if we are honest, a fare degree of hatred for those we perceive as our enemy. What makes them our enemy has nothing to do with any demographic group they do or do not belong to. Further, I don’t believe it is even their elite status. It is the dehumanizing actions that reflect their desire to tyrannize over us.

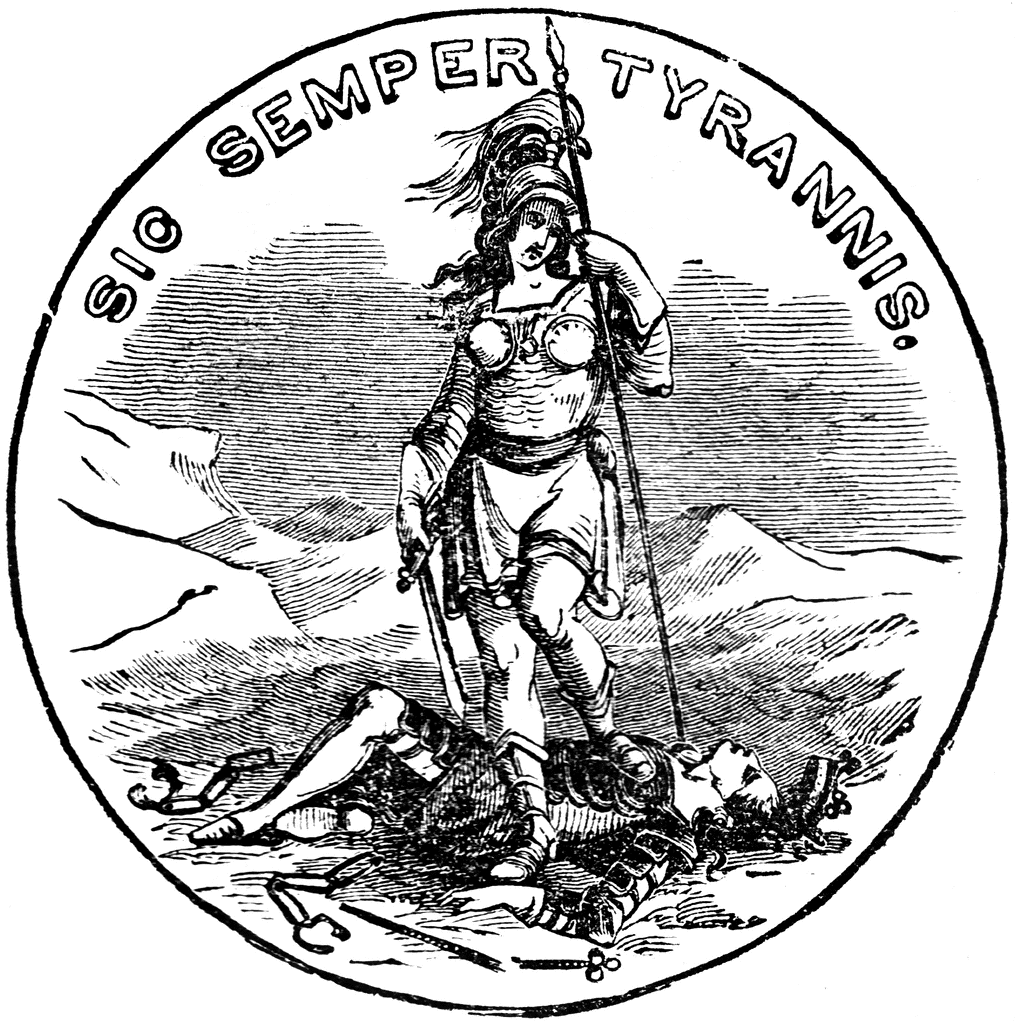

It is not for me to try to flesh out an entire mythology or Sorelian mythological image. However, I will venture to outline one concrete image that comes to mind. Given the global extent and multiplicitious nature of our contemporary tyranny, I would suggest a hydra straddling the orb of our globe. Of course, its many heads are well into the process of being severed by the sword wielded by a tyrannicide. If the motto sic semper tyrannis could be incorporated somehow, that would make me happy. What concrete action that image would be referencing, which would be the myth proper, yet eludes me.

This essay was first published on Nevermore Media's Substack

An interesting trend I've observed online is that Nietzsche is being cooped by certain elements who argue that common criminals and gang members are actually far closer to being the warriors Nietzsche extols than his intellectual defenders today. They similarly argue in favor of Islam and of mass migration to Europe because, in their view, Islam is stronger and more warrior like than the European people. This, of course, bothers other Nietzscheans because they argue Nietzsche doesn't just support random violence and that there is "good" (life affirming, noble, whatever) violence and "bad" (resentful, low class) violence. Unfortunately for the Nietzscheans, I don't think their system does a great job at distinguishing between good and bad violence or even good and bad people since it focuses so strongly on power, will, might makes right, and so on. I think you speak to that in the latter part of this essay.