The Day We Went to War Against Our Children

A Photo Essay for the 55th Anniversary of the Kent State Killings

A frequent visitor to Civil War battlefields becomes familiar with certain characteristic features of those fields and their memorialization. For instance, historical markers pointing out significant points on the battlefield.

When one visits a university campus, finding similar things, instead of signs pointing to the student union or the library, can be disconcerting to say the least.

A marker just above where a group of student protestors were gathered on May 4, 1970. Units of the Ohio National Guard advanced up this gentle slope towards the students, with some veering off to the right.

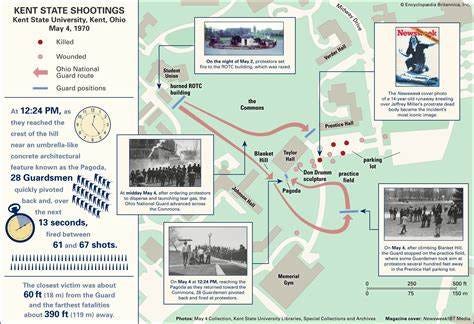

Likewise, one might study a map of the battlefield and note the major troop deployments before visiting, so as to have a general sense of where one is in the larger scheme of things as you move about the various areas of the battlefield.

The campus protests had been called after President Nixon announced the expansion of the Vietnam war into Cambodia on April 30th. Nixon had campaigned on bringing the war to a close. After the first day of protests (May 1st), around midnight, patrons leaving a bar in downtown Kent threw bottles at police cars and broke a bank window, causing the alarm to go off. The following Sunday morning, Kent State students would organize to go downtown to clean up the mess and make repairs.

On Saturday, May 2nd the ROTC building was set on fire. The arsonists were never identified. At 5:00pm, after receiving requests from local officials and law enforcement, Governor James A. Rhodes ordered the Ohio National Guard to deploy to Kent State. To this day, there are highways and government office buildings named to honor Rhodes.

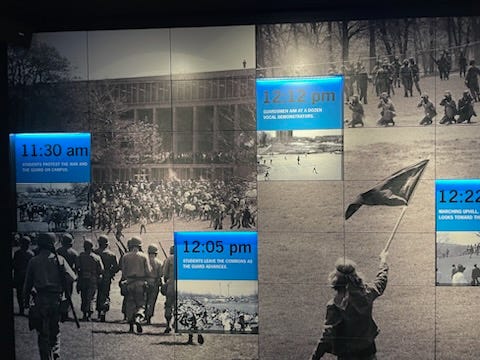

One may reference a timeline of the battle to understand how it unfolded.

On Sunday, May 3rd, the government distributed over 2000 leaflets warning students to discontinue protests. Government agents who had infiltrated student organizations also promoted calling off the protest scheduled for Monday.

When students were released from their morning classes on Monday, May 4th, they were surprised to find their campus occupied by military forces, including armored personnel carriers and over 300 soldiers under the command of General Robert Canterbury.

Oral history accounts later obtained from surviving students indicate that the students’ motivation for the protest expanded to include indignation that their campus would be occupied by the military aimed at revoking their First Amendment right to protest (which had legally been abrogated by Governor Rhodes’ declaration of a state of emergency).

Initially, students were ordered to disburse via orders given through a bullhorn. When they did not, the soldiers were ordered to chamber rounds in their rifles and affix bayonets. Next, the troops fired tear gas on to the common (the ‘grassy knoll’) where one group of about 300 students were assembled. Some students threw some of the canisters back towards the National Guardsmen (who were wearing gas masks) and also some rocks were thrown. One soldier reportedly required first aid due to being hit by a rock. A group of about 20 soldiers were ordered to kneel and take aim at the students with their rifles. These soldiers were not given the order to fire.

For some reason, the troops were broken into two groups with one advancing to the left of Taylor Hall, over ‘Blanket Hill,’ past the right of the assembled students. Further in that direction, a larger group of around 1,000 students were assembled. Around this time, the smaller contingent of soldiers realized they had basically taken a wrong turn, wandered around in a circle, and went back the way they had come. The students, interpreting this as a ‘retreat,’ assumed the soldiers were preparing to leave campus, and followed them.

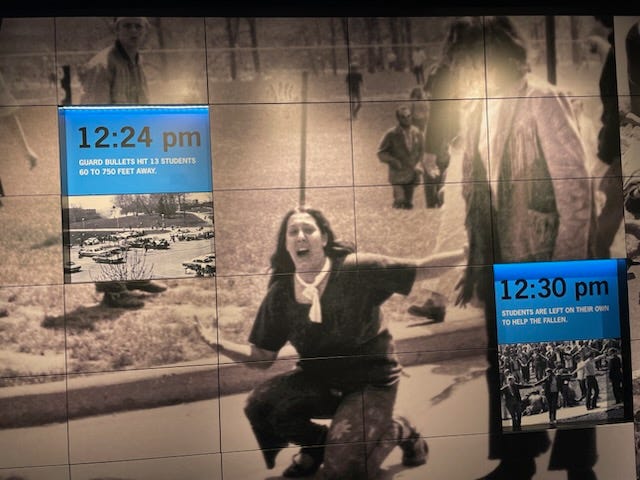

Possibly feeling ‘surrounded,’ at 12:24pm, at least 29 of the troopers turned to the oblique and fired their weapons, discharging at least 69 rounds into the students.

Four students were killed outright and nine more were wounded.

Moments later, a Kent State administrator, at the behest of the Guard commanders, begged the remaining students to disperse to avoid a ‘massacre.’ The students complied.

Every major Civil War battlefield has its cemeteries. Usually, the army left in possession of the field dug individual graves for their fallen comrades with the defeated being consigned to mass common burial.

At Kent State, while no students are buried there, the spots where the four fatally shot students fell are marked off. One such spot is shown here.

Upon seeing photos of the shootings, Neil Young wrote this angry protest song, recorded later that May by Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young.

Stephen Stills’ more reflective song appeared on the B-side of that 45. The interpretive video in the Kent State May 4 Museum utilizes this song, not ‘Ohio.”

For some reason, my favorite bookstore in Kent has a mural of Kropotkin drinking ‘a cup of freedom.’ According to the owner, no one any longer knows who that bearded guy on the wall is.

All photos from Kent State University were taken by the author whose daughter is currently a student there.

My PROTEST SONGLIST-‘OHIO’ is number 1.

I was in college then. The founder of The Sewanee Review, Andrew Lytle, gave me a ‘C’ on a story about KSU shootings I wrote the night of called, “Tin Soldiers”…Got A’s on the rest.

https://open.substack.com/pub/jeff515p0/p/mayday-mayday-mayday?r=1n8kl4&utm_medium=ios

One has to marvel at the dichotomy that a mere 55 years has produced in the national mindset. I long for the return to the ethos of that bygone era.