Aristotle v. Capitalism

An attempt at clarity

I’m writing this to succinctly summarize my philosophical thinking regarding economics. It is most immediately occasioned by a conversation with Michael Martin which was, in turn, a discussion of his recent essay ‘Sophiology v Socialism: An attempt at clarity’ (I honor him by structuring the title of my essay following his) and by exchanges with Domenic C. Scarcella who is a Good Neighbor.

It is not my intention to be exhaustive. Instead, I have opted for concision and a structure that will highlight the threads running through my thoughts and to develop out just a couple of sources I draw upon.

Further, especially in regard to the two above named gentlemen, this is not explicitly a critique of their positions, but a statement of my own. That should help us put a finer edge on any further discussion we might engage in.

Beyond the immediate occasion, I have found myself rather lonely the past five years, often alienated from critics to both the left and the right, for various aspects of my views which I hold to be essential and have not been persuaded to abandon (don’t get me wrong, I’m fine changing my mind, I just don’t like having it changed for me). Hence, a clear statement may help me better understand my own evolved views and make my position clearer for critics.

Aristotle

As with more things than not, the basis of my economic thinking is rooted in Aristotle. The main problem with the slender book by Aristotle entitled Economics (Oeconomica- literally, ‘household management’) is that it isn’t written by Aristotle and isn’t about what we normally think of as economics. Further, most of it is pernicious.

The work is, however, largely Aristotelian in its approach and though it comes to us under the authorship of ‘Aristotle,’ the first ‘book’ was probably written by a student or successor to him at his school. Of the two ‘books’ that comprise the work, the larger second book (apparently written by someone in Egypt or elsewhere in the Hellenized empire of Alexander the Great) is a nasty account of how various politicians have craftily and deviously succeeded in getting money out of their subjects (‘Aristotelian’ only in that it provides an empirical survey of various practices but lacking Aristotle’s moral commitments). Nevertheless, we must begin with what we have.

Well, why start with Aristotle if the source material is not great? Because he is my approach to an ethics of flourishing rooted in human nature. This allows us to develop an ethics which holds together with metaphysics and avoids the modern ‘fact-value dichotomy,’ which in turn allows us to formulate a substantive natural law theory. There might be other ways to do those things, but Aristotle is who I typically go with.

In the first book ‘economics’ is defined as household management (household is oikos in Greek). While modern economics is usually understood at a macrolevel, Aristotle suggests that it really starts in the household with either agricultural production or small craft production.

In his Politics Aristotle had said that the purpose of the family (household) was to reproduce human life. In the Economics it is associated with the Good Life, which was identified as the purpose of the Polis in the previous work. This is not really a contradiction. We might think of it like this: the immediate purpose of economics is for the family to provide the material necessities to sustain and reproduce human life within the broader community and contributing to our overall goal of Living Well (flourishing). Also, ‘Aristotle’ insists that the science of economics is prior to the science of politics because the household is prior to the city (see the concept of ‘subsidiarity’ discussed below).

Further, ‘Aristotle’ approaches economics as a ‘common’ activity because nothing is more natural, he says, than that man and woman should live commonly (having all things in common). This introduces an expressly normative element. This is developed by noting that agriculture is the most morally pure form of economic activity because it takes nothing away from anyone else and is, hence, the most just form of economics. Other modes of economics take something away from another, either with their consent or without it, ‘Aristotle’ observes.

At a metaphysical level, ‘Aristotle’ is dealing with human beings as ‘persons’ (not his term, but that has become common nomenclature in some modern forms of Aristotelian thought) as distinct from the modern liberal and capitalist ‘individual’ (the so called ‘economic man’). In this regard, the individual is an abstraction of modern political and economic theory which sees the single human as atomized, rational, and acquisitive. By contrast, ‘person’ denotes the single person as imbedded in their essential social relationships, especially the family and the city for ‘Aristotle’ (he also distinguishes between male and female, and slave and free).

In short, ‘Aristotle’ gives us an account of human economic activity developing in the household, cooperatively engaged in, aimed at human flourishing (that which is in accord with our nature), which then also entails the moral ends of economy.

Christianity

Saint John Paul The Great was a Christian personalist and, in Laborem Exercens, argued against the commodification of labor and for the rights of the worker.

My understanding of the human person is further informed by classic Christianity. On that view, the human person is created ‘in the image of God,’ and is, hence, of inestimable value. In this regard, and possibly no other, we are equal. This has the moral implication that to use a fellow human without due regard to their moral and spiritual status and their own human ends is both impious and evil. I accept Jesus’ admonition that the only proper relationship between us is to “love one another.” Politically and economically, I believe this entails, negatively, an ethic of non-domination, and positively, the duty to help one another achieve a flourishing life.

What is capitalism?

Capitalism likes to present itself as ‘natural’ or the only ‘realistic’ system that can work. When we look at the historical development of capitalism, this is exposed as obfuscation. What came to be called capitalism, and what I mean when I use that term, is the economic system that emerged in Western Europe, first and especially in Britain, out of feudalism, roughly from the 15th to 19th centuries (and nowhere else, and at no other time).

Hence, it is proper to look at how feudal economic relationships were changed into capitalist economic relationships. Very generally speaking these are what I see as the salient developments:

First, there was an intellectual or ideological development which revived ancient Roman legal understandings of absolute private property ownership. This had been replaced under feudalism with an understanding of mutual rights and duties (a serf might owe something to their Lord, but the Lord owed things to them as well), the existence of the commons (land held in common, usually used for the grazing of livestock, hunting and fishing, and collection of fuel) which provided access for the lower classes to the resources they needed to make their living, the existence of craft guilds which allowed skilled craftspeople to govern their own economic activity (setting standards of quality, fixing prices, etc.,), and moral restraints imposed by the Church and often codified in law, and always informing custom, to regulate usury, just prices, just wages, etc…’.

At a philosophical level, this developed out of the emergence of Nominalism (the denial that metaphysical essences exist, for instance ‘human’, and that only individuals exist, say Jack and Jane). Ironically, that was applied to economics and specifically the question of property by the Franciscans who wanted to be sure they weren’t owning anything, such as the food they were ingesting, which would violate their oath of poverty. Nevertheless, Nominalism provides the metaphysical underpinning of the triad of modernity: technological rationality, capitalism, political liberalism (individualism).

This new understanding of things allowed for different moral, legal, and economic principles to govern (and largely coincided with the emergence of the modern nation-state). The commons were ‘enclosed,’ that is turned into private property controlled by the large landholders. This made it very hard for peasants to live lives of subsistence. Further, with the balance of power decisively shifted to the owners of the land with no real duty to their ‘tenants,’ most of the tenants were ’cleared’ (making way for the shift to farming cash crops, especially sheep for wool, which did not take much labor and turned a better profit for the landholder).

Dispossessed and unable to economically survive without their traditional rights of access to the land and kicked off that land by the Lords, a large, displaced populace was formed whose only material resource was their labor. Without other options and combined with the application of steam power to machinery (industrialization) an urban working class was created. The craft guilds were destroyed or made irrelevant (typically by forbidding their meeting or ‘combining’).

Further, moral restraints on economic activity were held to be irrational and unnatural, so that only ‘market’ forces and financial realities (usury) were to determine the course of economic development.

Structurally, this creates a fundamental social differentiation of roles whereby some own the capital (land and machinery primarily) and some don’t and have to sell their labor to those who do. Last time I looked, every single ad of the 22,000,000 listed on LinkedIn (globally) was for a working-class job: sell your labor to someone who owns the capital.

The rationale operative is to efficiently exploit natural and human resources to produce as many commodities as possible as cheaply as possible. The mechanism of competition ensures that corporations tend to become larger and larger, forcing out smallholders of various sorts (for this reason, Chesterton argued that it was capitalism that was against private property, at least any ordinary people having much of it). Further, while the system is dynamic (it does produce a heck of a lot of stuff cheaply) it is also inherently unstable, requiring continual governmental cooperation, intervention, and stabilization.

The explicit or implicit goal of human economic activity is to acquire as much wealth as possible (‘market mechanisms’ do not work if people don’t act in their ‘enlightened,’ or unenlightened, self-interest). At most, the primary moral restraint is that exchanges occur through ‘voluntary’ contracts (however, the parties to those contracts seldom occupy equal positions of economic power, so the system is exploitive by its nature).

This economic system, later developed through a period of imperialism and now operating on a global scale under the domination of multinational corporations, international banking, national governments and international NGOs is what I mean when I speak of ‘capitalism.’

And I’m again’ it.

Modern Aristotelianism

As I see it, there are two main philosophical traditions of modern thinking in response to the development of historical capitalism that draw on the fundamental insights of Aristotle: Marxism and Catholic Social Teaching.

Marx

First, Marx starts with a conception of the human person similar to Aristotle. He insists that we see human beings as social beings, always already necessarily embedded in various social relationships. For Marx, those relationships include the relations between various economic classes within the existing economic structures of a particular historic period.

Further, Marx sees human beings as existing to fulfill their nature, what he terms their ‘species being.’ For Marx, this includes acting upon the world (laboring) so as to produce the material means that will allow for human flourishing. This includes access to sufficient material resources to live decently and cooperative relationships with those with whom we engage in economic activity. Further, humans need the space to be creative and develop their various human potentials (intellectual, physical, social, etc…).

As such, Marx famously envisioned an economic system which operated according to the principle: “from each according to his ability, to each according to his need” (which is modelled on Jesus’ descriptions of the Kingdom of God, especially in Matthew 25, and of the early church while it was filled with the Holy Spirit, as described in especially Acts 4).

Marx’s theory of ‘alienation’ helps us understand the impact of the system on the human person. The worker is alienated from the product of their labor. This means they do not own what they make (that belongs to the employer). Hence, they also do not control their laboring process: how they will work, when they will work, where they will work, etc… (for comparison think of how an independent farmer or craftsperson does control these factors). They are also alienated from others. Though the production process is necessarily social (large manufacturing enterprises, transportation networks, etc…), they are also competitors with every other person in the process- for a position, wages, etc…. Finally, they are alienated from their species being: they lack the material and social basis to fully develop their human potential.

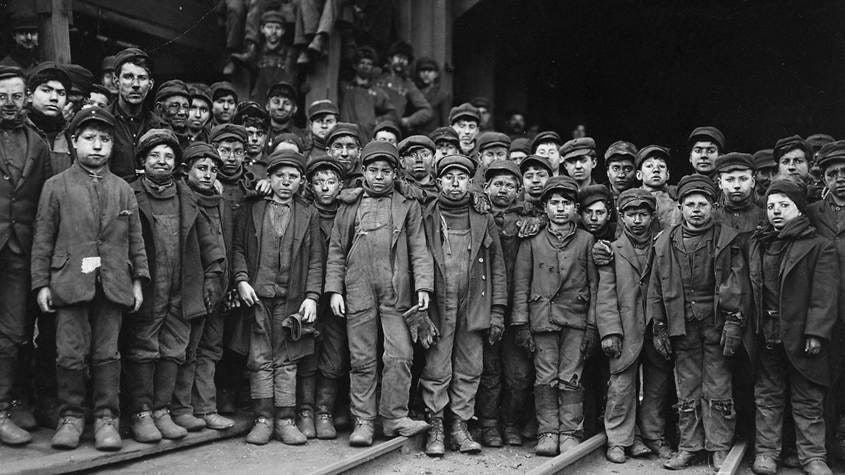

Historically, free-market, real, capitalism just loves child labor- absolutely requires a strong State to tamp it down.1

His theory of commodification presents a similar process at the macro level. In a capitalist economy things are not, strictly speaking, produced because they are needed or useful. Many people go without needed or useful things though the productive capacity is there. They are produced because they will sell on the ‘market’ (itself an abstraction disassociated from any actual community or local economy) and bring a profit. Hence, economic activity is divorced from the natural function of economy (supporting human flourishing) and subordinated to unknown pressures. This introduces a sort of falseness into economic life. It also calls forth things like advertising to artificially stimulate consumption of unnecessary (and often harmful) commodities. Further, capitalism fetishizes commodities, treating them as almost gods, allowing their possession or our quest for them to define our identities.

Additionally, the worker’s labor is also commodified. This means it must be sold on the market at the market rate. There is nothing about ‘the market rate’ that assures a sufficiency for decent living (hence, there is no inherent mechanism to ensure a just wage). It also means that we come to relate to ourselves as products to be exchanged.

Further, the market sees nothing outside of resources and commodities. Nothing is ‘sacred’ to the market. As Marx noted, “All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned…”.

Catholic Social Teaching

Catholic Social Teaching (CST) refers to the teachings of the Church, especially the moral teaching of the Popes, in the modern era in response to the development of industrialization and capitalism. This is usually seen as starting with Pope Leo XIII’s encyclical Rerum Novarum (‘of new things’, indicating capitalism’s recent emergence) in 1891. This tradition is explicitly rooted in the thought of Aristotle, especially as reconciled with Christianity by Thomas Aquinas. Hence it is guided by the two purposes of the human person: natural flourishing (happiness) in this life and eternal beatitude with God in the next.

From the beginning, CST sought to balance the claim to private property with the legitimate moral claims of the working class. Leo employed a pretty Lockean theory of property as the natural fruit of human labor. He situates this within a Natural Law tradition whereby we labor to gain our sustenance and what we have labored for is properly our own property

Within the tradition as it has developed this is understood as best operating under two contrasting moral goods (hence, making it a rather dynamic and adaptable moral framework): solidarity and subsidiarity. Solidarity recognizes the natural and moral fact that human economy depends on cooperation and mutual support. This provides a cohesive moral energy to bind communities together. On the other hand, the principle of subsidiarity picks up the Aristotelian notion that the family is prior to the village which is prior to the city. This is explicitly wielded against statist socialism (and an overactive state of whatever variety- what Hilaire Belloc termed ‘The Servile State’). The principle is that issues should be addressed and handled at the lowest social level possible and if a higher social entity abrogates responsibility for that, it has violated the rights of the subordinate entity. For instance, education is properly handled at the family and local community level: if larger governmental entities abrogate responsibility for education to themselves (which they have), they do wrong. This provides a decentralizing impetus to CST thinking.

The proper goal of economics and government in general is ‘the common good:’ the good of all the individual humans and individual social groupings (families, businesses, communities, associations, etc…) within the society. No private interest should be allowed to prevail over the common good.

This entails an understanding of ‘social justice.’ That is a much-maligned term because it was hijacked by the wokesters and snowflakes. It just means justice also applies at the level of a society (not just between individual persons). This entails the rights of human persons and communities to the things human beings need to flourish, including a ‘just wage’ which would allow for the ‘frugal’ sustenance of the worker and their family, the education of children, healthcare, political rights, etc…. Most importantly, CST talks of the ‘universal destination of goods.’ A lot is packed in there, but it is meant to ensure that economic activity occurs primarily to meet human needs. Explicitly this means that rights to private property are not absolute rights but are subordinate to the natural (and divine) purpose of goods to meet human ends. People contribute what they can but are entitled to what they need. CST envisions this occurring through the duty (not option) of ‘Christian charity’ whereby the needs of the poor are voluntarily met (you can also voluntarily choose not to meet them, but you probably go to hell). It can extend to political rights as well.

In case that does not make it clear where the Church stands, the notion of the ‘preferential option for the poor’ was developed. This is understood as the implementation of Jesus’ mandate in Matthew 25 to give special moral weight to the needs of the poor and marginalized. A society’s health is to be measured by how well it cares for the economically disadvantaged, ill, elderly, disabled, etc, not how many billionaires it produces or how many secret islands they bed minors on. In general, side with the underdog.

This does not (quite) equate to socialism. Defenders of capitalism will point out that the Church has explicitly denounced socialism (not mentioning the explicit denunciation of capitalism and usury). I think that misses the mark. The trend of the development of CST has been in the direction of increasing worker influence and rights. Leo defended the formation of trade unions (especially Catholic ones) when those were illegal in many Western countries. Later developments have called for worker involvement in corporate decision making. The ‘conservative’ Benedict XVI stated that “democratic socialism” “was and remains close to” Catholic Social Teaching. The Church is very critical of top-down, statist forms of socialism and all atheistic forms. Bottom-up socialism seems at least “close” to CST.

Roughly, you could say I appreciate Marx for his critique and trend towards CST for a prescription. Hence, I’m not a Marxist, but a student of Marx (and as such, I also have any number of critiques).

Alternatives to capitalism

Hence, a person who thinks in the categories and traditions I do, is going to be heavily critical of capitalism. What are the alternatives?

There is statist socialism: Communism and Fabianism (and to an extent the welfare state). This would combine economic and state political power in the exact same hands: the danger of dangers from my perspective. Morally and practically, I am opposed.

My only wee bit of reservation in taking it off the table completely is it could turn out to be the only possibly workable option in one possible future. If AI integrated robotics actually displace the large majority of human workers (as Elon Musk and an array of other tech moguls say it will) we will be in a position we have never been in before: human labor won’t be worth exploiting- the majority of us literally rendered economically useless. If that develops quickly, in the next 5-10 years as some predict, and if the majority of us are going to survive and retain any sort of dignity, that will require unprecedented political mobilization. I see no reason why those folks would share any produce with people they don’t need. While Elon is more starry-eyed (‘work will be optional’), Nvidia’s Jensen Huan is more honest (no commitment that hugely increased production will be shared with non-contributing people). I don’t see any grassroots, bottom-up, libertarian movements currently possessing anywhere near the raw power that would be required to distribute goods to meet human needs when all the means of the economy are owned by a tiny handful of powerful people and we aren’t needed even for production. A powerful state might be able to do that and might be motivated to do that. Even then, it would require massive popular mobilization to force them into doing it. I’m not banking on it, but it’s the only reason I wouldn’t take that option completely off the table.

Bottom-up, decentralized, socialism would include libertarian, syndicalist, and democratic socialism (that is, the varieties of socialism associated with anarchism or participative democracy). All of these seek to preserve the liberty and dignity of human persons (vs the collectivity), and local communities, while ensuring a distribution of economic goods to meet human needs. That balance is fairly appealing to me. Syndicalism especially envisions militant unionism (syndicates) and the coordination of those through a federal framework (I’m pretty pro-labor organizing and very pro-federalism and extremely pro-localism).

The two forms of economic organization most closely associated with CST are Corporatism and Distributism. Corporatism refers not the rule of corporations but to looking at society as a single, organic, body (corpus). It seeks to negotiate and balance the needs of the various components of society. Classically this would be the state representing the public interest, business representing its interest, and labor representing its interest. The idea is that if forced to negotiate in good faith, the common good should be allowed to prevail. This is sort of the ‘rightwing’ CST option. It is also associated with fascism. The problem is that the state seldom actually represents the pub lic interest, and while business will represent the interests of business labor unions can be corrupted to not represent the interests of workers. Hence, it often ends up with business and government fully cooperating and the labor dog being thrown an economic bone.

Distributism holds that private property should be held as widely as possible and centralized property in the form of large corporations, monopolies etc.. should be limited as much as possible (a friend who critiqued this essay prior to publication pointed out that Adam Smith was also critical of large-scale enterprises and corporations). In this regard, it has close links to the Jeffersonian yeoman ideal. It also relates to what I have been getting at in my The Faded Republic series under the notion of economic republicanism or extending civic republican principles to a modern economy. Further, as developed by people like GK Chesterton, Hilaire Belloc (pictured above), and various Catholic and Christian Democratic economists in the 20th century, it can accommodate cooperative and other forms of organization in entities that are larger than a family farm or small business. It would also entail measures to curtail usury, ensure just wages, etc….

So, what am I for?

I’m for human flourishing for everyone (Aristotle + Christianity, aka egalitarian anti-modernism).

I’m not for statist socialism or corporatism (except under extreme existential threat and if that is the only possible option presenting itself).

There is a lot in the various bottom-up socialist traditions that is helpful in providing a critique of actually existing historical capitalism. There aren’t many examples on a large scale and in a pure mode of it working and it is easy to see how it could go wrong. However, European social democracy was headed in this direction. The Scandinavian countries continue to dominate the ‘happiest countries in the world’ index year after year, though those models are not really applicable to a large and diverse country like the US. Syndicalism is a possibly useful component of an economic program. There is an historically strong tradition of socialist municipal governance in the United States (the ‘sewer socialists’ who governed around 150 cities and towns in the 1930s and 40s, often in alliance with Republicans- believe it or not; in fact, Republicans like New York’s Fiorello La Guardia sometimes ran on a Socialist or American Labor Party ticket).

Distributism (or Jeffersonianism or republicanism) is an appealing option. However, all the trends in capitalist societies are away from small-scale, largely family operated, enterprises. Wishing it weren’t so is not sufficient.

So, there is no ‘system’ or ‘ideology’ that I see as the ‘magic bullet’ to create a human, flourishing-directed, egalitarian economy. Really, I think it would have to develop out of the various contingencies of economic and political struggle and who knows where we’d end up exactly or how we’d get there precisely. However, it is good to have a moral aim in mind and access to theoretical resources that might point in the right general direction. I’m completely good with ‘things got better’ being the outcome vs. ‘we made it to utopia.’ Also, different peoples will move in different directions to somewhat different ends.

‘Better’ for me means smaller, more local, more human, more empowering of the people who do the work (the working class or farmers or small businesspeople).

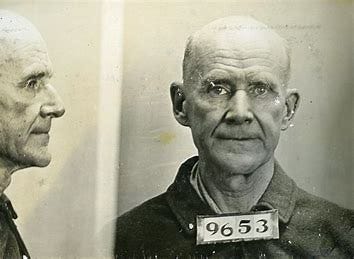

There have been good socialists: (to limit myself to American examples throughout) my favorites are probably Gene Debs (pictured above, in prison, from which he ran for President and got three and half percent of the popular vote), Mother Ann Lee (we just call her Mother), Woody Guthrie, the Wobblies (syndicalists), Red Emma (she can be a pain), the guy who wrote the Pledge of Allegiance, MLK (we call him Milk and he thinks it’s funny) and Dorothy Day (pictured at top).

There are plenty of good distributists (or whatever we call them): Tom Paine, Tom Jefferson, the nineteenth century Populists (especially William Jennings Bryan), Henry George, the Southern Agrarians, Wendell Berry.

Throw in Alisdair MacIntyre, Henry Thoreau, Walt Whitman, and a few others who aren’t easy to classify for good measure, and it’s a party.

If FDR was a corporatist, there is even some affinity there (better a New Deal than no deal during the depression). Factually, the mid-1950s to mid-1970s with a strongly ‘mixed’ economy probably provided the period for the most people to realize ‘the American Dream.’ Speaking of deals, Trump is probably also best understood as a weak corporatist (he is certainly not a free-market capitalist), but this party is not being held at Mar-A-Lago.

If we look hard, there are even some Communist types I’m ok with: WEB DuBois, Pete Seeger, Jack London, and Norm Thomas all had their good points.

It’s even good to mix in a few defenders of the Free Market: well, this is a harder one, but Ben Franklin knew how to party and was public spirited.

In fact, some version of this group assembles every Saturday morning in The Holler for coffee and hashing-out of ideas. We get together again on Sunday evening for Bourbon… and to listen to traditional folk music and have a hootenanny.

We all have a pretty good idea of what the good America, The Beloved Community, looks like, and we find the differences between us stimulating.

There are no shortage of songs I might share that relate to this post, but this is probably the most direct: I Hate The Capitalist System (from Alan Lomax’s Kentucky recordings back in the ‘30s). Sarah Gunning and her coal miner husband lost two children to harsh living conditions during the Great Depression. Eventually she lost her husband as well as he died of tuberculosis and was denied admission to a hospital. When she complained that their mining shack was too drafty, officials advised her to lay her husband under the floorboards.

The same reviewer mentioned earlier asked about children working on their parents’ farm in this regard. I don’t think that is a matter of greedy corporate exploitation of the kiddies- I think that is exceptionally good parenting. Work is not the problem- exploitation is.

Honored by the mention!

I think it's a problem of scale, for one. As history has more than proved, once a system gets too big the distinctions between capitalism and socialism disappear and the idealistic impulses that initiated them are perverted. That's probably why I prefer some form of distributism: it has "not getting too big" built into it. But we don't have that in the US and nobody else does either.

It was easy for Pete Seeger or even Dorothy Day to play communist. In a more or less democratic society, no one will stop them, if that's what they want to promote. But neither of them moved to a communist/socialist country--and for a reason.

So, since we live in a less than perfect society in a less than perfect world, I would choose to live in a capitalist society over a socialist (and I'm not talking about the ideal, but how they actually work in the world). As I mentioned before, you don't see the Amish--the most Christian anarchist players out there--fleeing to socialist or communist countries. And for a reason. They even voted for Trump rather than live out the demonic socialist nightmare the Democrats were and are promoting--and the Amish NEVER vote.

"If AI integrated robotics actually displace the large majority of human workers (as Elon Musk and an array of other tech moguls say it will) we will be in a position we have never been in before:"

My bet is that any advancements in robotics and AI will just be machines, that do what machines have always done, act as a force multiplier for human labor, ultimately, in terms of production anyway, making human labor more valuable not less.

I think the tech moguls promote the idea of robotics and AI replacing human labor because it's what they want to be the case, it's what they want their investors to think is the case, and it's what they want the public to think.

That last one might be nefarious. If they can get the public to think that this is the case they could use it as cover for devaluing labor, and cutting wages, through whatever means, maybe the usual offshoring, or importing cheap labor, or maybe they have something new up their sleeve, but whatever the case this supposed replacing of human labor by robotics and AI, would make a good cover story.